Neil Curry, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Satoko Watkins, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Curry, N., & Watkins, S. (2016). Considerations in developing a peer mentoring programme for a self-access centre. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(1), 16-29. https://doi.org/10.37237/070103

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

The paper outlines a peer mentoring programme at tertiary level in Japan, where it is still an uncommon practice. It will explain the context and reasons for its introduction; namely, expanding the range of services of a busy self-access centre. It will then describe what services we wish the mentors to provide which are compatible with the aims of the centre, and what skills we believe the mentors should possess, and what they need to be trained in to successfully deliver the service. It will then describe the research opportunities which this programme should provide.

Keywords: peer mentoring, self-directed learning, learning advising, self-access centres

This paper will describe the background to the implementation of a peer mentoring programme at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) beginning with a description of the reasoning behind the decision to implement it and its intended outcomes. Each stage of the implementation process will be documented to help determine whether the stated outcomes have been achieved in the context in which we operate, which will be outlined later, but mainly to ask the question of whether students can be effective in engendering good self-directed learning habits in their peers as part of a formally-administered scheme. Firstly, we will describe the particular context in which we work at KUISspecifically the role of the Self-Access Learning Centre (SALC), and how we aim to develop mentoring as an extension of the services we already offer to students in our roles as Learning Advisors (LAs).

Peer mentoring, for the purposes of the scheme being described here, is defined as a relationship between two individual students within a formal, monitored scheme. One student, the mentor, offers advice and support, with a view to the realisation of a specified goal of another student, called the mentee. It is now a very popular practice at many universities in the UK, for example (Collings, Swanson, & Watkins, 2015), although it appears that there are relatively few instances of its use in Japan. Before proceeding, we wish to make clear the distinction between peer mentoring and peer tutoring. We wish our mentors to act to support the goals of their mentees, offering advice which is in congruence with the principles of learner autonomy already practiced in the SALC, which will be explained below. Mentors will not act as teachers, giving instruction, but rather as peers who have an understanding of the needs of mentees, and will act as a motivating force.

It is envisioned that the scheme will act as a pilot in order to test its viability. As such, there are several points we are concerned with:

- Interest and uptake on the part of the student body, both in terms of wanting to mentor or be mentored

- Content and structure of the mentor training programme

- The degree to which the programme will deliver the required outcomes (for outcomes please see below)

- The best way to administer and support the scheme.

The Context

Learning Advisors at KUIS operate from the SALC, a purpose-built space providing materials and an environment to facilitate language learning. As advisors, we aim to encourage the development of skills and knowledge for autonomous language learning amongst the student body, which is done in 3 ways:

- Self-study ‘modules’ (voluntary course) for developing self-directing learning methods

- Taught courses on self-directed learning methods

- Independent consultation with learning advisors, through appointments or a drop-in helpdesk.

All of these ways involve personal interaction with learning advisors on an autonomous basis, which means that students are not required by their courses or teachers to use our services. We engage the students in a spoken or written dialogue to help them in such matters as setting goals for study, choosing suitable resources and learning strategies, building confidence and motivation, and basically anything related to self-directed learning. Our services are also mainly offered in English and the students are encouraged to use this language in the SALC; however, students may use Japanese if they wish. As a result, the service is used mainly by students who seek us out and engage with us. It may be possible that there are more students who would like advice on studying but may lack the confidence to engage with faculty members or to use English.

Mentoring at KUIS

The SALC is sometimes perceived as a place where more fluent learners congregate, which can be off-putting to some students, so extending our services to the wider university environment through peers may be fruitful. Peer mentors should be able to help spread knowledge of self-directed learning methods and help develop learner autonomy, as noted by Kao (2012). Additionally, Kao mentions that through the use of reflective dialogue to help other students, peer advisors also develop their own “sense of learner autonomy through the interaction” (Kao, 2012, p. 97). We hope that this type of self-reflection on learning practice will appeal to those of our students who wish to further develop their learning skills, or who are interested in a career in education.

The SALC has recognised the need for learners to consider affective factors in order to fully realise their potential for self-directed learning (Valdivia, McLoughlin, & Mynard, 2011). Therefore there is the additional desire to further develop the ideas put forward in Curry (2014), which are that as learning advising employs techniques used to encourage autonomy in learners, that are the same that cognitive behavioural therapists use for treating anxiety disorders, LAs are well-placed to help students who suffer from Foreign Language Anxiety, which is brought about by the fear of the potential negative outcomes of performing in a different language. Peer mentoring also utilises some of these same counselling techniques, and because concerns about what peers may be thinking about their abilities can be a major inhibiting factor for some learners to use language, it seems appropriate that a peer mentor may be an excellent choice to help a student overcome their FLA. The mentors in the training group will also be recruited on the basis of interest in wanting to help other students with this problem, and will be trained towards this end, the details and progress of which will be described in a later paper.

The Benefits and Concerns of Mentoring

The benefits provided by mentoring both to those being mentored and also to the mentors themselves have been described at length, and the aim here is to demonstrate how it is thought that students at KUIS will be helped by such a scheme. It will also describe some of the problems which can arise, and how we might hope to deal with them.

Several benefits of using peer mentors in academic settings have been noted. Firstly, mentored students indicate a superior academic performance, in addition to less anxiety displayed towards their studies (Rodger & Tremblay, 2003). Retention of students is also aided (Jacobi, 1991), dropout rates are reduced, and the mentee is helped to feel more involved in university activities (Colvin & Ashman, 2010). It is also very important to note the benefits which accrue for the mentors themselves. Among these are the feeling of reward gained through supporting others, “reapplying concepts in their own lives” (Colvin & Ashman, 2010, p. 127), which is to reassess their own situations through reflecting on the ideas they are providing to their mentees, and, lastly, the development of friendships and contacts. All of the above are highly relevant to students at KUIS, and it is hoped that through reflecting on their experiences and study practices, the mentors will be able to further develop their own self-directed learning skills in tandem with their mentees, as stated above. Everhard (2015) also points to an increase in “self-confidence and self-esteem” (Everhard, 2015, p. 306).

There are risks, however, as Colvin and Ashman (2010) also note. The danger of mentors over committing themselves is present, and it must be confirmed that they are able to spend time on mentoring, together with their other obligations. As personal issues may be involved, both parties might leave themselves emotionally vulnerable if they are obliged to ‘open up’ and divulge their feelings. Efforts to take a full part in the relationship are also required of mentees in order to make the partnership viable; they must be reliable and responsive during conversations, and make the effort required to reach their stated goals. Finally, complaints are reported about some mentees being over-dependent (Christie, 2014); for example, in the case of peer tutoring, students may request that tutors complete homework tasks on their behalf (Mynard & Almarzouqi, 2006).

In a Japanese context, in which great emphasis is placed on the widely-found hierarchical relationship of sempai / kohai, where a senior student advises a junior student, there may be the potential of a mentee deferring to the ideas of a mentor simply because they are older or in a higher year. Christie (2014) also warns that the positioning of the mentor as the expert in the relationship results in hierarchy, as the mentor is instructing the mentee how “to ‘fit in’ to the university culture” (Christie, 2014, p. 960). Kao (2012) advises that in order to alleviate any problems caused by the redefinition of roles which are more traditionally hierarchical, it is necessary “to take into consideration the learner’s socio-cultural as well as psychological factors” (Kao, 2012, p. 98). Thus, as well as selecting trainee mentors who are experienced in self-directed learning, we will be sure to emphasise, during the recruitment and training stages, the reciprocally supportive and beneficial nature of the mentor / mentee relationship. This will also have to be made clear to potential mentees when they apply to use the service. Like the learning advisors, student mentors will be attempting to help their mentees consider and choose their available SDL options according to their own needs, and not directly telling students what they should be doing.

Needs Analysis

Before designing the programme we thought it advisable to gather ideas and opinions from the student body about how they viewed the idea of peer mentoring, and also what they might want to mentor or be mentored about. We also thought that a survey could help raise awareness about peer mentoring.

A questionnaire was produced using the SurveyMonkey platform and piloted in July 2014 with the 28 members of our class, using both English and Japanese. Feedback indicated that the questions were clear and easy to understand. Subsequently, the questionnaire was distributed in November. It was sent to a total of 1677 students who were registered as SALC users, and we received a total of 383 responses.

The responses were analysed and categorized according to the content of the answers given. As well as serving the purpose of raising awareness of mentoring among the students, and possibly reaching out to those who might be interested in becoming a mentor, we were particularly interested in what aspects of learning and university life the learners felt it was important to have help and advice with. A summary of the results regarding the areas in which students want to / can give support is shown in the appendix.

From the results, it is possible to see that many of the students questioned felt that advice about ‘class registration’, or which courses they should choose, was most important. However, we considered it to be impractical for mentors to advise on this area as it would be unlikely that they would have enough knowledge about all the classes and teachers available; it would be better for them to be able to suggest where and how information can be sought. Similarly, exams such as TOEFL and TOEIC were also a concern, but it was decided that for now it would be best if the Learning Advisors handle such queries in the SALC, as there is already a TOEFL exam tutoring system in place.

Hence for the purposes of our project, namely to extend the reach of the SALC and to lay the foundations for any future mentoring program, we thought it prudent to concentrate on areas in which we would best be able to train would-be mentors, and which also fall under the purview of the SALC. This would namely involve advising learners on self-directed study and assisting with language anxiety-related issues. According to the survey, these are obviously of importance to some students.

In addition to the questionnaire results, it was also thought necessary to consider the results of the recent SALC Curriculum Project needs analysis study. In this study, there were six areas that students stated that they needed knowledge of to succeed in their studies (Takahashi et al. 2013):

- time management (e.g. scheduling, prioritizing)

- managing learning resources – human & physical (e.g. knowing how to access support from advisors/teachers, making contact with speakers of English, knowing how to access SALC facilities effectively)

- learning activities (knowing a variety of strategies, incorporating English into daily life)

- learning environment (choosing the right environment for the right task)

- attitude (e.g. motivation, endurance, effort)

- goal setting (e.g. prioritizing needs, breaking goals into achievable tasks)

These areas encompass the majority of the queries learning advisors receive, and therefore mentors trained to advise on these topics would be invaluable.

Defining the Roles and Characteristics of Mentors

Colvin and Ashman (2010) list several roles which student mentors could be expected to play. Below are the roles which we think are most relevant to our context, considering the needs analysis above, and also the skills which we believe our mentors will need to use.

Table 1. Roles & Characteristics of Mentors

Below are characteristics which Terrion and Leonard (2007) regard as necessary for successful mentors, and which we will be looking for during the interview process when looking for suitable candidates:

- evidence of academic success

- flexible schedule

- previous experience in mentoring

- aspirations towards self-enhancement

- good communicative skills

- supportive

- can act independently

- trustworthy

- empathetic

- enthusiastic and interested in other students

We have added some other characteristics which we think are also appropriate for our context:

- desire to empower their mentees

- proven experience in self-directed learning (e.g. completion of SALC courses)

All prospective candidates will be interviewed and references obtained from their teachers as to their personalities and academic performance.

Training Syllabus Content and Structure

The aim of the training course will be to help ensure that mentors will receive the knowledge and skills needed to effectively facilitate mentees’ needs. For example, as stated by Newton and Ender (2010), there is a great difference between the advice given by friends in daily life and the approach taken to advice giving in a mentoring situation. The mentors will need awareness of and some practice in the use of what may be a new set of interpersonal communication skills to function effectively. The following are what we hope the mentors will be able to achieve following the training course:

- Clearly define their roles as peer mentors and specify what they should and should not take responsibility for

- Understand and give own definition of learner autonomy

- Know what self-reflection and self-evaluation are, and practice regularly

- Be able to employ some learning advising skills in dialogues

- Be able to suggest various learning strategies and activities for different learning needs and goals

- Be able to suggest various learning resources for different learning needs and goals

- Be able to suggest campus resources that are connected with mentee’s needs

- Can show understanding of learners’ anxiety, confidence, and motivation and offer some strategies to deal with such issues

- Offer some strategies for time management

- Understand their work contract

The course will last for ten weeks and consist of single 50-minute sessions, with the possibility of additional time if we feel that some items need to be covered in more detail. Ideally, the sessions will be longer in the future, but currently we are obliged to run it during students’ lunch hours, and so time is limited.

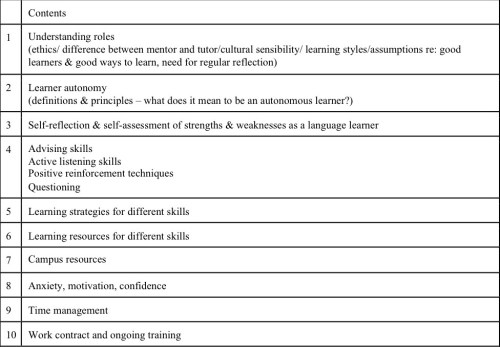

At the time of writing, the contents of the training sessions will be the next task for us to work on, but we have made a rough syllabus to guide us:

Table 2. Training Syllabus

Outcomes and Programme Assessment

In order to facilitate a smooth implementation of the scheme in the future, and to investigate to what extent the mentors are achieving the desired effect and that mentees are satisfied with the service, there are several questions we wish to answer as the scheme progresses. Each stage promises to present particular issues we will need to address and will require different methods of research.

In consideration of the above, we have selected the following as the outcomes which we hope to achieve:

- Mentees should

- feel an improvement in confidence or motivation

- feel less anxious about speaking English in and out of class

- feel that they are able to set meaningful and attainable goals

- feel better able to plan and organize their studies

- have a greater knowledge of available strategies and resources.

To summarise, they should be able to utilise self-directed learning skills to some degree, and feel a progression with their language skills. Additionally, we hope that by using the mentoring service, they will become regular SALC users.

- Mentors should

- feel an improvement in their own self-directed learning skills. They will have regular meetings with the project coordinators where they will reflect on their mentoring and any insights they have gained about how other learn, which we hope they will then be able to apply to their own learning. They will also be encouraged to share their experiences and knowledge with each other.

- feel able to achieve other personal goals relating to their mentoring (to be discussed with us). Many students are interested in careers in teaching and therefore want to expand their knowledge and experiences in education. Others are interested in improving their communicative skills, for example confidence speaking with new people, active listening abilities, and widening their circle of friends.

- The Programme administration should

- ensure the reservation service works smoothly

- verify if procedures for handling any issues / complaints are functioning

- evaluate whether the service is being promoted effectively.

In addition to the above, the following is an outline of the research we plan to undertake in order to determine if the outcomes have been realised:

Table 3. Research Focus

The amount of detail and information that each stage of the project will produce will be quite large, and as a result it is necessary to keep the project on a small-scale while we determine its long-term potential. Accordingly we anticipate hiring a small (6-8) number of mentors. It will also be necessary to institute an effective system for evaluating the outcomes at a later point.

Next Steps and Final Thoughts

To establish the project we have agreed upon the following timeline:

- 2015 semester 1 (April to September): Plan content of training sessions and recruit trainee mentors. Arrange administration procedures.

- 2015 semester 2 (September to mid-January): Conduct mentoring training, review content of session, decide on advertising strategy

- 2016 semester 1: Publicise and begin mentoring service, conduct some reminder training for mentors. Begin collection and analysis of data on the programme’s efficacy.

In subsequent papers, we hope to provide more detail on each of the different stages of the programme. We feel that a successful self-access centre should not only be seen as a space for learning but also as a community, creating a sense of ownership in the students. This means that ownership would not only extend over control of language and the learning process, but also could extend the notion of self-access learning beyond the SALC and the purview of the Learning Advisors (Everhard, 2012). Having students themselves engage in the advising process will be a great way to increase their involvement, in addition to increasing our resources by utilising their valuable skills and experiences.

Notes on the Contributors

Neil Curry has been teaching in Japan for 9 years and is currently a learning advisor at Kanda University of International Studies. His primary interests are in FLA and self-directed learning.

Satoko Watkins holds an MA in TESOL from Hawai’i Pacific University, USA. Her research interests include learner development and empowerment.

References

Christie, H. (2014). Peer mentoring in higher education: Issues of power and control. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(8), 955-965. doi:10.1080/13562517.2014.934355

Collings, R., Swanson V., Watkins, R. (2015). Peer mentoring during the transition to university: Assessing the usage of a formal scheme within the UK. Studies in Higher Education, 3, 1-16. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1007939

Colvin, J. W., & Ashman, M. (2010). Roles, risks and benefits of peer mentoring relationships in higher education. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 18(2), 121-134. doi:10.1080/13611261003678879

Curry, N. (2014). Using CBT with anxious language learners: The potential role of the learning advisor. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(1), 29-41. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/mar14/curry/

Everhard, C. J. (2012). Re-placing the jewel in the crown of autonomy: A revisiting of the ‘self’ or ‘selves’ in self-access. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(4), 377-391. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec12/everhard/

Everhard, C. J. (2015). Implementing a student peer-mentoring programme for self-access language learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(3), 300-312. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep15/everhard/

Jacobi, M. (1991). Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 61(4), 505-532. doi:10.3102/00346543061004505

Kao, S. (2012). Peer advising as a means to facilitate language learning. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context, (pp. 87-104). Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Mynard, J., & Almarzouqi, I. (2006). Investigating peer tutoring. ELT Journal, 60(1), 13-22. doi:10.1093/elt/cci077

Newton, F. B., & Ender, S. C. (2010). Students helping students: A guide for peer educators on college campuses. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Rodger, S., & Tremblay. P. F. (2003). The effects of a peer-mentoring program on academic success among first year university students. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 33(3), 1-18.

Takahashi, K., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., Sakai, A., Thornton, K., & Yamaguchi, A. (2013). Needs analysis: Investigating students’ self-directed learning needs using multiple data sources. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal 4(3), 208-218. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep 13/takahashi_et_al/

Terrion, J. L., & Leonard, D. (2007). A taxonomy of the characteristics of student peer mentors in higher education: Findings from a literature review. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 15(2), 149-164. doi:10.1080/13611260601086311

Valdivia, S., McLoughlin, D., & Mynard, J. (2011). The importance of affective factors in self-access language learning courses. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(2),91-96. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun11/valdivia_mcloughlin_mynard/

Appendix